Baked Coatings, like the name says, baked coatings onto metal parts for various businesses. Some of the coatings were for colour, others were for durability, and there were other purposes too. The important thing was that all these coatings had to be baked onto the metal parts, and that meant everything needed to go through the oven.

The fact that everything had to go through the oven meant that Baked Coatings implemented an assembly line system. The line – actually a moving chain of hooks – moved at a constant speed, which meant it went through the oven at a steady rate. As parts were prepared, they were hung onto the hooks, coated for durability, colour, waterproofing, or whatever purpose was needed, and then eventually rolled through the oven.

That was also how they measured the output of the system as a whole. Baked Coatings would simply count the number of hooks that had something hanging on them out of the total number of hooks that went through the oven in a given period. If the percentage was high, then the oven was operating at close to full capacity.

According to those numbers, Baked Coatings was doing well. The percentage of loaded hooks that went through the oven was consistently well over 90%, which was about as high as it seemed reasonable to expect. If they wanted to expand operations, they were going to need another oven.

And that was where the trouble started, because Baked Coatings did want to expand: they had a good product, and a sales team who were, and promised they could, sell as much as the factory could deliver. But a new oven would cost well over a million dollars, which was a big investment even for a successful business. Could they squeeze a few percent more out of their existing setup before they had to invest in expensive new machinery?

To answer that question, Baked Coatings started looking at all the things which could cause a hook to go into the oven without anything hanging on it… And what they found shocked them.

It turned out that the line of hooks only moved at a constant speed when it moved it all. Any of the operations before the oven could halt the line if they fell behind, and the line spent more time halted than anyone was happy with. There was no point in moving the line if there was nothing to put on the hooks, after all. A high percentage of hooks that went into the oven had something on them, but that was only because the line of hooks sat idle a lot of the time. This meant the oven – the single most expensive investment in the entire production chain – was operating at far less than its possible output.

Unfortunately, there were lots of reasons why the line might stop moving. If a shipment of parts hadn’t arrived from the suppliers, there would be nothing to go on the hooks at all. Sometimes, two shipments arrived at once, so the line had to be paused while everything was unpacked and prepared for the coatings. Other times, an urgent order for a batch of a particular coating was needed, so the line was paused while the urgent order was put through the oven. There wasn’t just one bottleneck, there were dozens, and which one was most important seemed to change almost every hour. The supervisors were working hard trying to keep things moving.

A lot of the bottlenecks could be resolved by adding more staff at the places that got overloaded, but that had its own problems. For one thing, the cost of adding all these resources was far more than the budget allowed. And for another, it never seemed to help as much as it should. When one of the operations wasn’t overloaded, the extra staff had to find something else to do. Nobody wanted to be seen standing idle, which was fair enough. But that meant they were often partway through a different job when they were actually needed for their original task. Every time they had tried it in the past, Baked Coatings somehow ended up with more staff, half-finished jobs everywhere, and still no increase in output!

The worst offender, it turned out, was the spray area where parts received their coatings before going into the oven. It wasn’t really their fault: they were doing their best, but there were only three sets of spray equipment. And it took time to change a set of spray equipment to do a different coating, clean it from the last coating, attach the new heads, spray the parts, and then do the whole thing again with whatever came down the line next. So, of course, they got backed up, and of course, they had to stop the line – anything that went into the oven had to be coated, or there was no point in putting it through the oven at all.

An intense set of conversations began at that point. Some said that the oven was still the limiting factor, because everything had to go through it. Other people said that the spray equipment was obviously the true problem, because that was limiting how much could go into the oven in any given time. There was even a group who said that the sales team were causing all this, because they were accepting too many small orders for different kinds of coating.

Eventually, they agreed on a solution. In the future, they wanted the oven to be the limiting factor for their operations. They wanted it operating at full speed constantly, with a full load at all times. Until then, however, the spray area was the limiting their output, so that was where they had to focus their attention. That meant everyone else had to do what they could to increase the output of the spray area.

Another set of spray equipment, and the people to operate it, would be brought into the business, which would still cost much less than installing another oven would have, and would significantly increase the amount of time the hooks spent moving. Baked Coatings was also going to start paying attention to the output of the spray area as well as the oven.

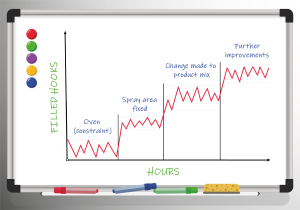

Tracking the spray area’s output and comparing it to the oven’s output, and them comparing both with the output of the business as a whole, proved that they were right. When the oven was running for more hours, more customer orders got fulfilled. And if things flowed more quickly through the spray area, the oven could run for more hours. At the start of the tracking, oven usage was actually around 50%. After some improvements to the spray area, the oven usage immediately jumped to 70%, and then kept climbing. Baked Coatings had managed to significantly increase the output of its system as a whole, simply by finding out what was really limiting its output and addressing that.

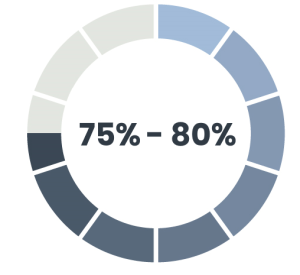

More improvements quickly followed. Not all coatings needed to be in the oven for the same length of time, so sending everything through at the same speed meant some things were being baked for far longer than they needed to be. Changing the mixture of products that went into the oven meant they could also speed up the line sometimes, which increased output even further. Doing batches of products that required the same coating, where it made sense and wouldn’t occupy the oven for too long, also meant the spray equipment needed to be changed over less. That sped things up again. The running time of the oven was now between 75% and 85%, and the average was slowly increasing.

Baked Coatings had noticed a change in how the operators and supervisors felt about their jobs, too. Before starting this process, the supervisors were held responsible for low output through the oven, and blamed when things weren’t good. That hadn’t been fair, but they also hadn’t been able to prove why. Now, with everything being oriented in terms of getting more through the oven, their true value was being acknowledged. The operators in the spray area could see how much difference they could make to the output of the oven, and felt good about increasing overall output. Many people were looking, and finding ways to make things flow more smoothly too. Staff morale was also improving as an extra benefit.

It turned out that finding their rate-limiting step was one of the most profitable things Baked Coatings had ever done!