It was going to be one of those days. Antoine was Chief Operating Officer at Viewpoint Industries. Since getting to work 40 minutes ago, he’d already been given a dozen maximum-priority interventions to make. Everything had looked good when he left work last night, but now he wondered what had gone wrong. Where had all these issues come from?

Viewpoint Industries made refrigerators and freezers, but it seemed like nothing ever turned out how it should.

When Bernie opened the door to the office he shared with Antoine, Antoine pretended to glare at him.

“You’re the factory manager, Bernie,” he growled. “Have you looked out there this morning? We don’t actually make refrigerators; the only thing that gets produced is chaos!”

Bernie pulled up a chair and sat down. “I know. We’ve been friends for 12 years, and we have this discussion every few months. Each time you say the same thing about getting control of the chaos, and each time we attempt to improve our control we get a temporary win, and then it all somehow goes back to how it was. If you’ve got something new, then tell me. If you don’t, then let me grab some of those troublesome tickets off you and I’ll get out of here while you grumble.”

Antoine pulled a face. “Don’t go just yet. Look, what happened the last time we made some changes?”

“The same thing that happens every time,” Bernie replied. “We start making changes, it turns out those changes cause disruptions, these disruptions compound the more we do, and we end up having to abandon them. I don’t like saying this, Antoine, but maybe this is as good as it gets. Maybe this is actually a pretty good system.”

There was a loud beeping sound from outside, and Bernie got up again. “That’ll be the truck. Let me just get the loading underway, and I’ll be back in ten minutes.”

But Bernie wasn’t back in 10 minutes. In fact, Bernie didn’t make it back before early afternoon. The goods to go on the truck had been blocked in by some half-finished jobs, and those jobs had been left half-finished because everyone working on them had been reassigned to finish an urgent order for a major customer. By the time he got back to the office, Bernie looked tired.

Antoine pushed a paper bag towards him. “Here. I got you some lunch.”

“Thanks.” Bernie took a big bite from the sandwich. “Right. Now, what were we talking about this morning?”

“About how to actually get control of things out there, instead of running around putting out fires. I think you’re right, we always end up disrupting everything. So, what if we don’t do that? What if we try to limit the disruption: just work on one bit of it, fix that, and then move on to the next one?”

Bernie shrugged. “It might work,” he said between mouthfuls, “But it seems a bit pointless. Suppose we manage to get the Inwards Goods side of things running smoothly – how much difference would it really make overall? My worry is that it would take forever to see any real benefits. And if it’s going to take a long time then we might as well not bother at all, because by the time we’ve finished, everyone will have forgotten why we started in the first place, and everything will have reverted anyway.”

Antoine glared at Bernie again. “Well, what’s your suggestion? Things can’t keep on like this!”

“They have so far,” Bernie said, then held up his hands in mock surrender. “OK, OK! I agree. Seems like we’ve got a big problem, though. We want our solution to be endorsed and supported, so we need to show benefits from it quickly. That means we need a solution for the whole business. But we also need to limit the disruption from our solution, so we also need to just do a bit at a time. How do we show a compelling benefit quickly, and still minimise the disruption we cause?”

“I… don’t know,” Antoine admitted. “Look, let’s leave that aside for the moment. You were down in Shipping this morning, right? What do you find goes wrong there?”

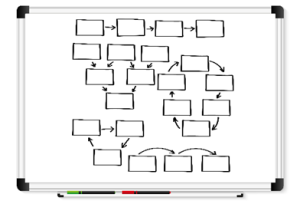

Bernie had plenty to say about what could go wrong just with the process of shipping finished goods to customers, and Antoine wrote it all down on the whiteboard in their office. He clustered similar problems together, highlighting the disruption they caused, and drew arrows between the clusters to show when in the system they occurred. Eventually, he stepped back.

“I can’t think of anything else,” Bernie said. “Heh – it looks kind of like a flowchart, now. Boxes, with arrows going everywhere, and I see there is some overlap in the where the problems show up, that makes sense.”

Antoine nodded. It did look a lot like a flowchart. Flowcharts didn’t just have boxes and arrows, though. They also had diamonds, which indicated choices or checks… Antoine blinked. Surely it wasn’t that easy, was it?

“Bernie,” he said quietly, “A flowchart is like a schematic, right? Like a design for how things should work. It tells us where to monitor for risk.”

“Yep,” Bernie said. “What’s your point?”

Antoine took a deep breath. “It wouldn’t be all that hard to come up with a master view that shows how things flow around here, right? How jobs flow through the business, I mean.”

Bernie shrugged. “No, it probably wouldn’t be all that difficult. I don’t really see how it would help, though. We already know how things work around here – badly. We need something that gives us more control.”

“But everyone would recognise it, wouldn’t they?”

Bernie nodded.

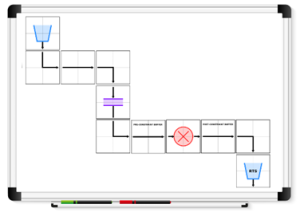

“And we could also make a flowchart for how we want things to work, including the points in the flow we would monitor so we can act pre-emptively, with precision, and stay in control,” Antoine continued, “And what would be different.”

He grabbed a different coloured whiteboard pen and started adding more symbols to the whiteboard. “For example, what if we started looking for risk here, just before everything gets taken to the loading dock… if we see losses showing up here, that’s a sure sign we’ll have more problems to deal with in the next few hours. It would help to have some advance warning, right?”

Bernie grinned. “Yeah!” he said happily. “And we could also monitor… here,” he said, sketching in another control point near the start. His face fell. “Antoine, this is great for coming up with a solution, but how does it solve that big problem? You know, the one where either everything gets disrupted, or we don’t show any benefit?”

Antoine was grinning now too. “It solves it, Bernie, by avoiding it entirely.”

“Antoine, I have no idea what you’re talking about. Did you drink too much coffee?”

“Nothing like that! We draw up a schematic of how our products flow. Then we draw up a schematic of what our solution would change, the control points, and we show them both to people. They’ll be able to see the difference our solution makes…”

“… So they can see the benefits from it, even if we only do a bit at a time,” Bernie finished. “This is brilliant. In fact, I think we can make it even better.”

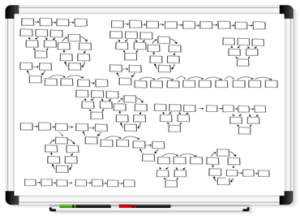

Bernie moved over to the whiteboard and started writing and drawing. “That schematic works for most things we do; all our ‘base’ products. But if we want it to cover everything, we need to add some more to it.” He kept writing and drawing for several minutes, while Antoine watched. When Bernie had finished, he’d nearly filled the entire whiteboard. Antoine had to stand at the other side of the office to take it all in, and when he did, he sighed.

“Bernie, come over here and take a look at your masterpiece.”

Bernie walked over, then turned around. They both looked at the whiteboard, then they looked at each other.

“It’s a bit… cluttered, isn’t it?” Bernie said eventually.

“Yep,” Antoine nodded. “Too cluttered. So badly cluttered that it’s more or less unusable, in fact.”

Bernie sighed. “I suppose I’d better take all those additions off.”

Antoine thought for a moment. “Maybe not, let’s check… Do we need all these additional control points? How many of them are actually addressed by the existing control points? Let’s check, surely we do not have that many exceptions, the differences between refrigerators are not that great.”

“Yeah, that could work,” Bernie agreed. He went back to the whiteboard and made some changes. Bernie noted that some refrigerators were larger, some used different compressor types, some required different finishes, but almost all went through similar steps, and most of the additional control points were versions of the same in-common control point. “Looks better now, right?”

“Much better, Bernie.” Antoine said. “You know, this could help in other ways too. As it is, we can show the benefits of the solution, and minimise the number of changes and any adverse disruption caused, just by detailing the few control points we will install. Having the low-complexity schematic to refer to also means the solution is less likely get reverted.”

“And Bernie, if it works for operations, I see no reason it can’t work in other areas too. The sales team, for example, it has a lot of moving parts, and Catherine has been wanting to improve the flow there for some time now. Too many opportunities are being lost due to our tardiness.”

Bernie grinned. “Sounds good to me,” he said. “Do you think we can get control with this?”

“I don’t know,” Antoine said, “But it’s a good start, isn’t it? Let’s get to work. I have a feeling that once we finish rationalising the control points it will all go much smoother.”